Special Report

Report Information

Pakistan Flood Impacts on Agriculture & Food Security

Published September 18, 2025

For access to all reports, please visit the Archive.

Please visit the Referencing Guidelines page for information on how to cite the Crop Monitor reports and products.

Highlights

A combination of heavy monsoon rains since late June, cloudbursts, and recent water releases from overflowing dams has resulted in record flooding across eastern Pakistan, with some areas recording the worst flooding in over four decades, resulting in deaths, widespread displacement, and destruction of infrastructure, farmland, crops, livestock, and food stocks.

Punjab province is the breadbasket of the country and has been the worst affected by the flooding, and in recent weeks, over 2.9 million people have been evacuated in Punjab province alone. Other impacted areas include Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and Balochistan.

Pakistan is one of the world’s leading rice exporters, and Punjab province produces over half of the total national rice output, followed by Sindh province.

Damage occurred to Kharif season rice crops that were submerged during critical development stages, particularly in Punjab province. Satellite-based analysis shows a significant reduction in rice area in early September 2025 compared with September 2024. However, by September 17, the impact of the flooding decreased, suggesting some crop recovery. An estimated 220,000 hectares of rice were flooded from August 1 to September 16, but the overall damage this season is likely greater due to earlier flooding in areas where farmers were not able to replant.

Damage also likely occurred to maize, cotton, vegetables, sugarcane, orchards, and other crops in the field at the time of the flooding.

In addition, there is concern for planting of the upcoming Rabi wheat season, which commences in late September, due to flood-related losses to agricultural supplies and seeds as well as damage to irrigation infrastructure.

Overview

Since June 26, heavy monsoon rains, flash floods, and large water releases from dams have impacted many areas of Pakistan, particularly in the main crop-producing province of Punjab as well as parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and Balochistan [1,2]. Above-normal rainfall was observed across most parts of the country during August, particularly in north and northeastern areas of the country [3]. In the last week of August, unrelenting monsoon rains and subsequent water releases from upstream dams in India triggered severe flooding across the north and eastern districts of Punjab, including Lahore, Sialkot, and Gujrat. For the first time in decades, the Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers had simultaneously high to exceptionally high water levels [4]. Both Pakistan and India share several major rivers, including the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej. Following torrential rains that raised water levels to dangerous amounts, Indian authorities opened all gates of major dams in portions of Kashmir region on August 27 and issued a warning to neighboring Pakistan regarding the threat of downstream flooding [5].

Heavy rain and dam releases from India continued through early September, resulting in rising water levels and flooding in parts of Punjab and Sindh provinces. On September 4, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) of Pakistan issued a “high flood” warning for Kasur, Okara, Pakpattan, Lodhran, Vehari, Multan, Muzzafargarh, and Bahawalnagar districts, located in east and southern areas of Punjab province, with rising water levels continuing in the Sutlej River [6].

Through September 9, Punjab’s eastern rivers remained dangerously high, with the Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Panjnad rivers all swollen. These widespread floods have inundated large areas of cropland, particularly along the riverbanks (See Figure 1). As floodwaters reached further downstream, Sindh province also experienced significant flooding in September and was on high alert for a potential “super flood” with surging Indus River flows. The Indus River swelled at Guddu and Sukkur Barrages on September 9 and 10, with inflows exceeding outflows [7,8].

While isolated extreme rainfall events may lead to urban flooding through mid-September [3], floodwaters have begun to recede, coinciding with the typical withdrawal of the Indian Summer Monsoon in late September and early October [9,10]. As of September 15, river flows in eastern Punjab had returned to normal on both the Chenab and Ravi, and displaced families were beginning to return home [11,12]. However, water levels of the Indus and Panjnad rivers remain at a very high level, with floodwaters advancing into Sindh province, where 150,000 people have been evacuated and large areas of farmland and riverine villages have been submerged [13,14]. Additionally, as of September 16, elevated river flows from upstream areas and waterlogged soils are sustaining the risk of ongoing or renewed flooding in parts of Punjab, Sindh, and neighboring areas of Balochistan provinces [10].

Overall, Punjab province has been the most affected and has recorded the worst flooding in over four decades [15] Some of the heaviest flooding was along riverine areas where large swaths of land were inundated. In recent weeks, 2.9 million people across Punjab have been evacuated, and this number is expected to increase as rains and additional flooding are forecast to continue in some areas through September (See Rainfall Outlook Pg. 3) [10]. The floods have caused significant damage to infrastructure, livelihoods, crops, livestock, and food stocks. This year’s floods come just two years after the unprecedented 2022 monsoon rains that triggered catastrophic damage to agricultural areas and destroyed 2.6 million hectares of standing Kharif crops in Sindh, Balochistan, and Punjab, from which the country has yet to fully recover [16]. However, the overall flooding extent this year is not as severe as in 2022, particularly in Sindh and Balochistan [9].

Figure 1: Flooding along the Chenab River in Punjab, Pakistan. Sentinel-2 satellite imagery showing significant flooding along with Chenab River in Punjab, Pakistan between August 27th and September 3rd 2025.

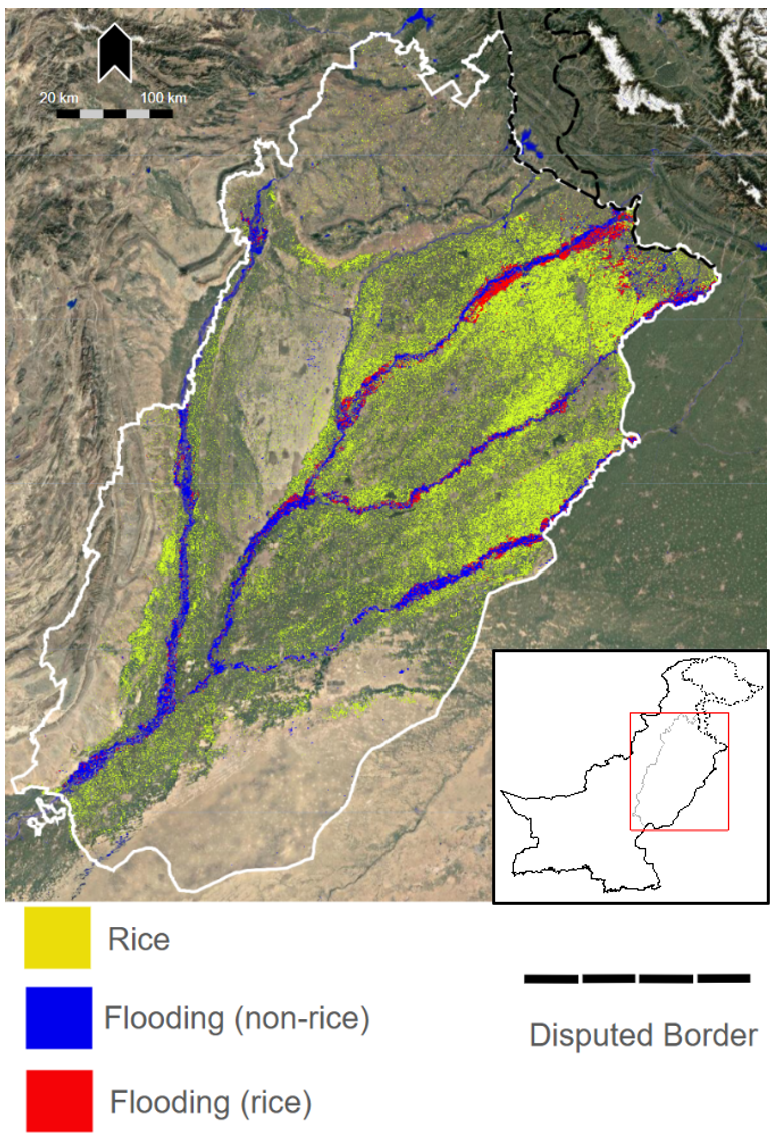

Crop and livestock losses are expected across Punjab and neighboring provinces for the current Kharif season, particularly for rice. Satellite-based analysis indicates that an estimated 220,000 hectares of rice were flooded from August 1 to September 16 (See Figure 2). Rice is a key export crop, especially Basmati rice from Punjab, and flood damage raises concerns for rural incomes and local markets. While the flooding in Pakistan and neighboring areas of India could have minor implications for the global market, rice supply remains stable as strong exports from India, Thailand, and Viet Nam will likely offset any losses from Pakistan, and high 2024 global rice production has weakened demand and lowered prices.

Additionally, maize is a key crop for poultry feed and also faces a risk from flooding, and both poultry and direct livestock losses will further strain rural livelihoods. Furthermore, there is some concern for future wheat production, Pakistan’s staple crop, as farmers may struggle to secure seeds and inputs needed for the upcoming 2025/2026 Rabi planting season, and damage to irrigation infrastructure could impede crop development. However, adequate wheat reserves and stronger macroeconomic conditions suggest that food security impacts are expected to be short-term and localized, unlike the more extensive impacts seen following the 2022 floods [9].

Figure 2: Rice flooded area extent in Punjab, Pakistan from August 1st to September 16th. NASA Harvest rice area (yellow) using Sentinel 2 and the Harmonized Landsat Sentinel datasets (S. Baber, A., Qadir). The max flooded area extent was mapped using a combination of NASA LANCE NRT 2-day flood composite and Microsoft AI for Good flood model from August 1st to September 16th. Flooding over rice areas is shown in red while flooding over non-rice areas is shown in blue.

Agricultural Impacts

Pakistan has two major agricultural seasons, including the Rabi (winter) season that extends from October to May and produces mainly wheat, barley, chickpeas, and lentils, and the Kharif (summer) season that extends from April to October and produces mainly rice, maize, cotton, and millet, as well as other crops [9]. The Kharif season coincides with the summer monsoon rains, which typically occur from late June through September, with peak rainfall in July and August. Punjab is the largest rice-producing province in Pakistan, and over the last 5 years during the Kharif season, Punjab has accounted for over 65 percent of rice production, 88 percent of maize production, and 84 percent of cotton production, while Sindh has accounted for 26 percent of rice production and 14 percent of cotton production (See Figure 3).

This year, planting of the 2025 paddy crop commenced in June, and overall rice planting was estimated at an above-average level, driven by high domestic prices at planting time. However, heavy rains and severe localized flooding in late June and early August negatively affected rice crop development in the Chenab and Sutlej river basins, requiring replanting. The floods and landslides particularly affected north and northwestern areas, including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, as well as parts of Punjab, Sindh, and Baluchistan provinces, resulting in crop losses and disruption of agricultural livelihoods [2, 9].

Figure 3: Spatial distribution of in-season Kharif cropped area in Punjab and Sindh (left maps) and percent of total Kharif crop production by province (right graph). Left: Spatial distribution of Kharif cropped area by crop type (rice, maize, fruits and vegetables, cotton, and sum of crop areas) in Punjab province (North) and Sindh province (South). Right: Bar chart showing the fraction of total in season Kharif crop production by province, with Punjab province (gold bars) and Sindh province (purple bars) comprising the majority of Kharif crop production, followed by all other provinces (white bars). Source: Crop Reporting Service, Agriculture Department Punjab and Sindh via the FEWS NET Data Warehouse

In addition, satellite-based indicators are showing a significant drop in vegetation conditions (NDVI) from late July through mid-August compared to average, followed by an increase in NDVI from mid-August onwards, reflecting an improvement in vegetation conditions (See Figure 5).

Figure 5: NASA Harvest Agrometeorological Graphic showing satellite-based indicators of rice crop conditions over Punjab, Pakistan as of September 13th 2025.

In addition to the damage to Kharif season crops, planting for the upcoming Rabi season, which commences in late September and early October, could be impacted by the recent flooding. Many farmers lost essential agricultural inputs, including seeds and other supplies, and combined with damage to irrigation infrastructure, farmers will likely be in need of support to complete Rabi wheat planting. The majority of Rabi wheat is grown in Punjab province (77 percent), and about 70 percent of this wheat is grown under irrigation [18]. While sufficient water availability in reservoirs will have a positive impact on irrigation and power generation, flood-related damage to irrigation and transportation infrastructure raises concerns for the upcoming Rabi wheat season production and subsequent transport to markets [3,9]. Additionally, fields are still inundated in some areas, which may disrupt land preparation and planting activities if the waters do not recede in time.

Comparatively, standing waters from the 2022 record floods reduced planted area for Rabi crops in localized low-lying regions of Sindh and Balochistan, and there was concern that seed and fertilizer shortages, along with flood damage to machinery and irrigation infrastructure, would further disrupt planting across the country [19]. However, the record floods receded on time for plantings in most areas, and coordinated efforts of the government and donor community ensured an adequate supply of seeds and fertilizers, resulting in near-average plantings for the 2022/23 Rabi season [20].

Figure 4: Comparison of rice area change in rice dominant Sheikhupura and Faisalabad districts for September 30, 2024 (left), September 5, 2025 (middle), and September 17, 2025 (right) using Sentinel 2. Rice is demonstrated by the red color.

Severe monsoon rains continued during August and into early September, coinciding with a critical development period for rice, and severe flooding impacted large cropping areas across eastern Punjab and downstream areas of Sindh.9 At that time, rice crops were transitioning from the late vegetative stage to the critical reproductive stages of panicle formation, booting, flowering, and early grain filling, which are stages that are especially vulnerable to flooding and submergence. Severe losses are expected for the Kharif season rice crops, and damage may also have occurred to maize, cotton, vegetables, sugarcane, orchards, and other crops in the field at the time of the flooding [17]. Satellite-based analysis indicates a significant reduction in rice area in Punjab province as of September 5, 2025, compared to September 30, 2024, particularly over rice-dominant Sheikhupura and Faisalabad districts. However, the impact of the flooding decreased by September 17, 2025, suggesting some crop recovery (See Figure 4). In addition, an assessment of rice flooded areas from August 1 to September 16 indicates an estimated 220,000 hectares of rice were damaged by flooding in Punjab, particularly in Sialkot and Narowal districts and along the banks of the Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers (See Figure 2). Overall seasonal damage is likely greater due to earlier flooding in late June and July, after which some replanting occurred but may not have been possible in all affected areas.

Rainfall Outlook

Very high precipitation amounts in eastern Pakistan and upper basin drainage areas in northern Pakistan and in northwestern India have resulted in severe flooding in eastern Pakistan and along the Indus River. Forecasts of continued above-average rainfall heighten flood risks into September.

The 2025 summer monsoon season has brought widespread above-average rainfall to the Pakistan-India region (Figure 6 top-left). Seasonal rainfall totals will likely range from 150 to higher than 200 percent of average in eastern Pakistan (eastern Punjab and eastern Sindh) and northwestern India (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand). In the especially wet areas, these amounts would typically occur around once every 15 to more than 43 years (SPI values > 1.5 and > 2.0, respectively), based on the CHIRPS version 3 1981-present data. 2025 rainfall totals are among the highest on record in eastern Punjab province of Pakistan and in locations across northwestern India (Figure 6 top middle-left). These amounts are based on a rainfall outlook for June 1st to September 20th, 2025, that includes CHIRPS final data for June and July, preliminary data for August and early September, and a 15-day unbiased forecast from September 6th.

Flooding in Pakistan could worsen before the end of the monsoon season. Above-average rainfall is forecast for September 9th to 23rd in Sindh and southeastern Balochistan (Figure 6 top middle-right). Southern locations could receive especially high rainfall amounts for that period, from 75 mm up to 300 mm in some areas. September rainfall totals will likely be above average across northwestern India and portions of eastern Pakistan, based on the SubC 30-day rainfall anomaly forecast from September 4th (Figure 6 top right). In northwestern India and northeastern Pakistan, following a week with drier-than-average conditions, above-average rainfall will likely return for the latter part of September, according to the ECMWF forecast from September 9th. Increased chances of above-normal rainfall in northeastern Punjab and southeastern Sindh are also forecast by the Pakistan Meteorological Department (Figure 6 bottom-right). Normal September rainfall is forecast in most areas of the country, with increased chances of below-normal rainfall in northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Kashmir.

Summer monsoon rainfall has been overall less extreme in 2025 than in 2022 in Pakistan (Figure 6-bottom left and middle), when above-average rain across a third of the country led to massive flooding, particularly over Sindh. A feature of the 2025 summer monsoon has been very wet conditions across much of northern India, including in areas that drain into the Indus River basin, and intense rains in Punjab, Pakistan. During the 2022 monsoon season, abnormally high rainfall occurred in western and central India and in central and southern Pakistan where lower Indus River basin areas were directly impacted.

Figure 6: Seasonal rainfall outlook anomaly and rank, 15-day and 30-day forecast rainfall anomalies, and seasonal rainfall anomaly comparisons for 2025 and 2022.

Top: Left and middle-left: Both panels are CHC Early Estimates, which compare current precipitation totals to the 1981-2024 CHIRPS3 average for respective accumulation periods. These show the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) (left) and historical rank (middle-left) for June 1st to September 20th, 2025, using CHIRPS3 Prelim for August 1st to September 5th and a 15-day bias-corrected forecast (CHIRPS3-GEFS) for September 6th to 20th. The SPI is an index that expresses how much precipitation at a location deviates from the historical distribution of observations, standardized so the relative extremity of values can be compared across regions and time scales. Blue (red) colors correspond to above-normal (below-normal) precipitation, and deeper shades indicate greater departures from the norm. Large SPI values of +/- 2 correspond to ~ 98th percentile amounts, which would be expected to rarely occur– approximately once every 43 years. The rank outlook shows areas where the precipitation total ranks within the wettest or driest in the CHIRPS historical record. Middle-right: A 15-day CHIRPS3-GEFS (unbiased GEFS) forecast anomaly from September 9th, 2025. Right: Average 30-day precipitation forecast for September 4th to October 4th by Subseasonal Consortium (SubC) models, from September 4th, 2025. From https://chc.ucsb.edu/monitoring/subx.

Bottom: Left and Middle: These panels compare the current season (2025) precipitation anomaly outlook (left) to that of a previous flooding event which occurred in 2022 (middle). Both anomaly maps are for June 1st to September 20th, relative to a 2001-2020 CHIRPS3 average for the same accumulation period. The 2025 accumulation uses preliminary data for August 1st to September 5th and a 15-day bias-corrected forecast (CHIRPS3-GEFS) for September 6th to 20th. Right: Forecast probability of September 2025 rainfall tercile, from the Pakistan Meteorological Department’s multi-model ensemble-based September outlook.

Source: UCSB Climate Hazards Center

Food Security Impacts

According to the latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) analysis, carried out prior to the floods in 2025, about 10 million people were estimated to face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 [Crisis] and above) between April and July 2025, down from 11 million people during the November 2024 to March 2025 period. However, recent floods are expected to cause negative localized food security impacts, following widespread displacement and destruction of farmland, crops, livestock, food stocks, and infrastructure. According to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), monsoon flooding since late June has killed more than 900 people nationwide. In Punjab province, 2.9 million people have been evacuated, with an estimated 80,000 now living in relief camps, and another 150,000 have been evacuated in Sindh province [10,14,21]. Widespread displacements are expected to cause direct income losses for poor households through both crop and labor disruptions [9]. However, as of September 4, many villages remained fully inundated, preventing aid organizations from conducting needs assessments until flood waters fully recede [6].

Flood damage to rice crops poses risks to rural incomes, as 60 percent of the population lives in rural areas [9]. While rice is less significant than wheat in terms of domestic consumption, it serves as a key cash crop and is largely exported, particularly Basmati rice from Punjab, and damage to these crops will further strain rural household incomes and disrupt local markets [22]. There may also be minor impacts to global rice markets as Pakistan is amongst the top ten exporters and was the fourth largest rice exporter globally in 2023 [9,23]. However, global rice supply remains stable due to strong exports from other countries as well as high 2024 production amounts.

While not significant in terms of human consumption, maize is an important feed crop, with about 65 percent of maize production used for poultry feed in Pakistan. This year, maize plantings were forecast to be below average due to low farmgate prices, which prompted some farmers to shift away from maize towards vegetables and cash crops. Additionally, maize losses from the flooding are expected to increase the future price of feed and could have implications for poultry production [2,24] The floods have also directly killed 6,508 heads of livestock, including at least 5,460 heads in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province [6,10]. Livestock losses could have significant implications for rural household incomes, impacting both direct earnings from the sale of animals and animal products, as well as secondary benefits such as access to milk and meat for consumption and draught power and manure for farming [25].

Additionally, food stocks, especially those from the recent 2024/25 Rabi wheat harvest, are vital for maintaining household food security and overall availability but were likely impacted by the flooding. Wheat is Pakistan’s staple food, occupying 43.3 percent of the total planted area and contributing between 46 and 72 percent of daily caloric intake. Pakistan is the eighth largest global wheat producer but not a major exporter as wheat is mostly consumed domestically [9,24] Flood damage to some storage facilities in Punjab has disrupted markets, causing sharp increases in wheat and flour prices by an estimated 40 percent in major cities [26–29]. However, overall reserves are currently estimated to meet national requirements, following a favourable 2024/25 Rabi wheat season harvest that was about 5 percent above average [30]. Additionally, the Punjab government recently imposed a ban on the use of wheat in feed mills which will remain in place for 30 days until October 3 [31,32]. The primary impact of the flooding on the domestic food supply would likely be a potential reduction for the upcoming 2025/26 Rabi wheat planting season, which commences in late September and early October, due to limited access to agricultural inputs and irrigation as a result of the flooding.

Despite direct flooding impacts to Kharif season crops as well as the potential wheat impacts for the upcoming Rabi season, adequate wheat reserves from the previous Rabi season, along with improved macroeconomic conditions, including stronger foreign exchange reserves, a stable rupee, and easing food inflation, have improved Pakistan’s ability to absorb flood-related shocks. Widespread or prolonged food security impacts are not expected, particularly in comparison to the more extensive floods in 2022. The current floods are only expected to result in short-term, localized, and acute food insecurity in affected areas [9].

The flooding is also expected to impact household income from agricultural labor and crop sales. In Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, agricultural and casual farm labor are key income-generating opportunities. Poor households are expected to see reduced income from the upcoming Kharif crop sales and labor opportunities this year, though the upcoming Rabi season will provide renewed labor opportunities in October. In comparison, after the more severe 2022 floods, floodwaters receded prior to the winter season planting activities, and labor opportunities had normalized by the following April due to widespread rebuilding efforts [9] The situation is changing rapidly, and additional monitoring is needed in the coming weeks to understand the full extent of the flood impacts.

References

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #8 (As of 11 September 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-8-11-september-2025 (2025).

FAO GIEWS Country Brief on Pakistan -. https://www.fao.org/giews/countrybrief/country.jsp?code=PAK (2025).

Outlook for September 2025. Government of Pakistan Pakistan Meteorological Department Islamabad https://rnd.pmd.gov.pk/assests/monthly/Sep_2025_outlook.pdf (2025).

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #4 (As of 30 August 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-4-30-august-2025 (2025).

India releases water from dams, warns rival Pakistan of cross-border flooding, says source | Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/india-releases-water-dams-warns-rival-pakistan-cross-border-flooding-says-source-2025-08-27/.

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #6 (As of 04 September 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-6-04-september-2025 (2025).

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #7 (As of 09 September 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-7-09-september-2025 (2025).

Pakistan’s Sindh braces for super flood as Punjab toll rises to 60, millions displaced. Arab News https://arab.news/phkjm (2025).

Food security impacts of 2025 floods in Pakistan. FEWS NET https://fews.net/sites/default/files/2025-09/Targeted-Analysis-Pakistan-092025.pdf (2025).

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #9 (As of 16 September 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-9-16-september-2025 (2025).

Flood survivors in Pakistan’s eastern Punjab return home as waters recede after weeks of devastation - TRT Global. https://trt.global/world/article/0eceefb2a275.

Pakistan’s nationwide monsoon death toll surges to 985 as floods head downstream | Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/2615323/pakistan.

Correspondents, O. Punjab rivers recede as flood enters Sindh. The Express Tribune https://tribune.com.pk/story/2566946/punjab-rivers-recede-as-flood-enters-sindh (2025).

Pakistan: More than two million evacuated from deadly floods. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn0xjd7wvy1o (2025).

Pakistan: Monsoon Floods 2025 Flash Update #5 (As of 02 September 2025) - Pakistan | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-monsoon-floods-2025-flash-update-5-02-september-2025 (2025).

Crop Monitor for Early Warning No. 76. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/636c12f7f9c2561de642a866/t/6564e6f4b0e0cc066e0f1be0/1701111541705/EarlyWarning_CropMonitor_202210.pdf (2022).

Jadhav, R., Shahid, A. & Shahid, A. Flood-hit India, Pakistan face rising basmati prices amid crop losses. Reuters https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/land-use-biodiversity/flood-hit-india-pakistan-face-rising-basmati-prices-amid-crop-losses-2025-09-08/ (2025).

USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Pakistan: Crop Progress Report. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) International Operational Agriculture Monitoring Program https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/pdfs/Pakistan/Pakistan_December2009_MonthlyReport.pdf (2009).

Crop Monitor for Early Warning No. 79. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/636c12f7f9c2561de642a866/t/65677b44c9c589216e9a90f6/1701280583254/EarlyWarning_CropMonitor_202302.pdf (2023).

Crop Monitor for Early Warning No. 80. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/636c12f7f9c2561de642a866/t/65677b5282e47c3f558d7208/1701280596023/EarlyWarning_CropMonitor_202303.pdf (2023).

Ahmed | AP, A. T. and M. Over 120,000 evacuated from central Pakistan as floods leave survivors in scorching heat. The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/09/09/pakistan-floods-evacuations-punjab/28f30b3e-8d57-11f0-8260-0712daa5c125_story.html (2025).

Ilyas, I., Sangi, U. A., Nusrat, S. & Tariq, I. Potential of Rice Exports from Pakistan. https://tdap.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Exploring-Potential-of-Rice-Exports-from-Pakistan.pdf (2022).

Harvest2Market. https://harvest2market.nasaharvest.org/.

USDA Grain and Feed Annual. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Grain+and+Feed+Annual_Islamabad_Pakistan_PK2025-0003.pdf&utm (2025).

Livestock Development Strategy; Rawalpindi Economic Growth Strategy. https://urbanunit.gov.pk/Download/publications/Files/20/2024/Livestock.pdf?utm.

Wheat crisis looms in Pakistan after Punjab floods destroy 30 percent of stocks. Arab News https://arab.news/8vrs3 (2025).

Desk, N. Pakistan faces potential wheat flour price surge as stocks fall below annual demand. Profit by Pakistan Today https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2025/08/29/pakistan-faces-potential-wheat-flour-price-surge-as-stocks-fall-below-annual-demand/ (2025).

Naveed, A. Wheat and flour prices soar as floods hit Pakistan hard. Daily Times https://dailytimes.com.pk/1364609/wheat-and-flour-prices-soar-as-floods-hit-pakistan-hard/ (2025).

Pakistan: Punjab floods push up wheat and flour prices as supply chains buckle; twin cities see sharp spike. https://ukragroconsult.com/en/news/pakistan-punjab-floods-push-up-wheat-and-flour-prices-as-supply-chains-buckle-twin-cities-see-sharp-spike/ (2025).

Crop Monitor for Early Warning (202507). GEOGLAM Crop Monitor https://www.cropmonitor.org/crop-monitor-for-early-warning-202507.

Pakistan Rejects Plans To Import Wheat, Citing Sufficient. https://www.tradeworldnews.com/pakistan-rejects-plans-to-import-wheat/ (2025).

Pakistan Confirms No Wheat Imports as Domestic Reserves Meet Demand. Grain Journal https://www.grainjournal.com/article/1104841/pakistan-confirms-no-wheat-imports-as-domestic-reserves-meet-demand (2022).

Additional Information

Prepared by members of the GEOGLAM Community of Practice Coordinated by the University of Maryland with funding from NASA Harvest

The Crop Monitor is a part of GEOGLAM, a GEO global initiative.

Disclaimer: The Crop Monitor special report is produced by GEOGLAM with inputs from the following partners (in alphabetical order): CHC UCSB, FAO, FEWS NET, Microsoft AI4G, NOAA, NASA GSFC, UMD, and WFP. The findings and conclusions in this joint multiagency report are consensual statements from the GEOGLAM experts, and do not necessarily reflect those of the individual agencies represented by these experts. GEOGLAM accepts no responsibility for any application, use or interpretation of the information contained in this report and disclaims all liability for direct, indirect or consequential damages resulting from the use of this report.